"Foundations" (Daguerreotype)

Lindsey Beal is a photo-based artist in coastal Rhode Island where she teaches at Rhode Island School of Design, Massachusetts College of Art & Design and the New Hampshire Institute of Art's MFA program. She has an M.F.A. in Photography from the University of Iowa and a Certificate in Book Arts at the University of Iowa’s Center for the Book. Her work can be found at Boston's Panopticon Gallery, Miami's Dina Mitrani Gallery and Portland's 23 Sandy Gallery. Her work combines historical & contemporary women’s lives with historical photographic processes. She is interested in the photograph as object and often includes sculpture, papermaking and artist books into her work. Her work has been shown at national museums, galleries & universities, including recent solo shows at the Griffin Museum of Photography and Danforth Art Museum. She has been featured on Lenscratch, LensCulture, Light Leaked, & Don’t Take Pictures and has been published in Diffusion, The Hand, Square Magazine, View Camera and 500 Handmade Books Volume Two. She recently earned a travel grant from Duke University and the Juror’s Award for Medium Festival’s “Size Matters” exhibit.

"Figure #19" (Ambrotype)

- When and why did you first start using alternative photographic processes in your work?

LB: I originally worked in silver gelatin and then color film, first printing in the darkroom and then scanning my film. When I was applying to graduate school, I knew that I wanted to learn alternative photography but I didn’t know that I would end up working pretty strictly in those processes! Two things were the catalyst for that. First, I was working all-digitally in my “Reproduction(s)” series and missed the tactile and physical work of the darkroom. This lead me to go back into the darkroom but working with historical photographic processes, as well as with printmaking, artist books and papermaking. Secondly, through studying the history of photography (which I love!), I was frustrated by the lack of explanation of what these processes were and how they were done. While there are some great videos now created by the George Eastman Museum and the like at the time, I wanted to see how these iconic images were made--not a short summary in the margins of a textbook or as a label on a slide. I think if you see how a daguerreotype was made, it makes the history of photography so much more real and you appreciate how hard it was to get those first images.

"Ball Grip" (Ziatype)

- How has your work evolved and changed throughout the past few years?

LB: My work continues to explore combining historical photographic processes with women’s lives past and present and has recently focused on how women use technology for pleasure. I am also exploring clothing such as corsets and stays that changed women’s bodies, as well as historical OB/GYN tools used in delivering babies. However, I recently opened up this idea of how the past is present that runs through my work by looking at how social media is similar to the Victorian practice of keeping commonplace books. So this idea of technology and how the past & present overlap, could be something I continue in future work.

"Diaphragm" (archival digital)

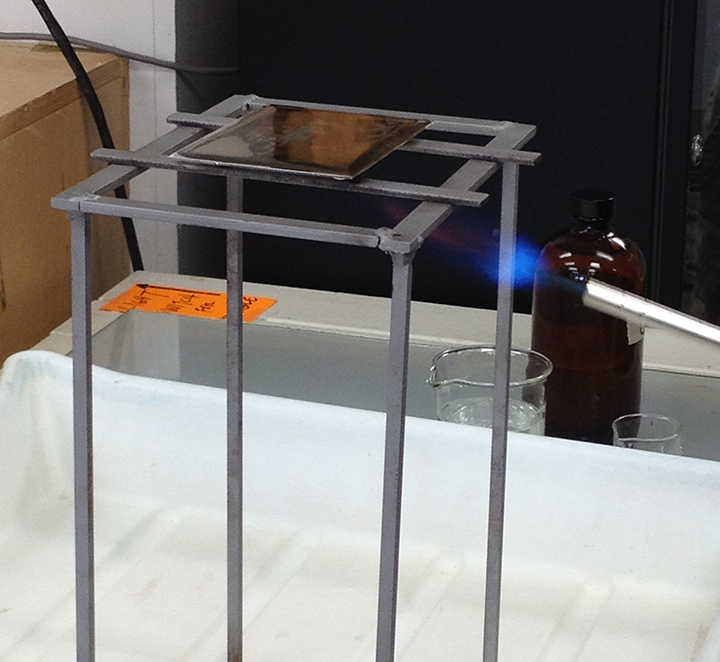

- You recently attended a workshop on Daguerreotypes taught by Jerry Spagnoli at Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina. Can you give us a look into that week learning this historical process?

LB: Penland is incredible and I would highly recommend it to anyone who wants to learn a new craft or process, or to get inspired by working with instructors who are world-renown in their craft and to be with other like-minded creatives. The daguerreotype (becquerel) class was the shortest session I attended at Penland (one week!) to learn this intensive process. But Jerry is an incredible educator and we all came away with some incredible plates and a firm grounding in the process. Generally, at Penland there are demos all week so you get a comprehensive education in the process and then practice it yourself with guidance by the instructor and studio assistant. In the evenings, there are artist talks, open house & art openings and plenty of time for inspirational conversation. One thing that is a strength for a place like Penland, is that there is a lot of room for collaboration with the other studios and with your classmates. I have attended three times and have seen some beautiful collaborations between photography and the book arts & letterpress studios.

- Tell us a little bit about your current solo exhibition at the Danforth Museum of Art in Framingham – how did the exhibition come to be & how did you work on the installation? In a way this show is a retrospective for you and it includes most of your projects – how do the individual pieces interact with one another as a whole?

LB: I was first introduced to the Danforth with their call for entry for their photo biennial two years ago when Francine Weiss juried the show. That show, artist talks and openings introduced me to so many in the New England photography community, (many who have become close friends). Jessica Roscio is the amazing curator there and we got along so well, bonding over photo history and early women photographers. We stayed in touch, meeting a few times with my new work. As curator, she invited me to be in a show she was curating on the interior and domesticity. This summer I brought all of my work to the museum and we went through it, with Jessica pulling work that worked together and addressed the show’s theme of making the private public. You are right that “Private Lives, Public Spaces” is a retrospective (minus my cyanotype work) and for me it is pretty amazing to see all of my work in one space. Although all of my work addresses past and present women’s lives, usually using historical photographic processes, I compartmentalize my work into separate series. To have them all interacting with each other in one space was overwhelming in a positive way. The dialogue that occurs between the series in the way that Jessica installed and curated it brings out the common themes of the work.

"Venus Figurine" (handmade paper & bell jar)

- Because your work is rooted in alternative photography how does presentation come into play? For example your “Transmission” series are all presented in Petri dishes with gold metal labels fixed to the frame. Do you have the end exhibition in mind when you first begin a project?

LB: Since I began working in photography, I wanted to present prints in a non-traditional format that encourages viewer interaction or creates pieces that act as three-dimensional objects. Early on, I created installations using fabric and scrolls or silver gelatin prints. From there I created wallpaper from my photographs to completely cover a space. Even my wet plates from my “Venus Series” were originally installed unframed on a picture rail that blended in with the gallery wall. I create the prints first with the idea that they will altered in some form or turned into objects. The work’s content needs to fit with the installation or sculptural process so some time and research is needed with the prints. For example, with the “Transmission” series, I took cyanotypes and created circular prints, embedding them in resin within a glass Petri dish. From there, I took inspiration from Victorian natural history museums and the way they present specimens using glass and wood cases. I mounted the plates with copper wire in shadowboxes and used the Latin names of each STD which were engraved on brass name plates.

"Bacterial Vaginosis" (cyanotype embedded in resin & petri dish)

- How has modern technology played a role in your approach to such historical processes?

LB: I incorporate digital photography, editing software like Photoshop and inkjet printers to print my negatives into the historical processes I use. Although I work in historical photographic processes, traditional bookbinding and papermaking, for me, these processes can still utilize contemporary technology. These processes force me to slow down and focus on the process, yet with digital technology, I can slightly speed up my workflow. Being able to use digitally edited images and printing them as negatives through an inkjet printer onto materials like Pictorico film gives people the option to go back into the darkroom. In this way the historical and the contemporary can be easily combined.

"The Electric Coronet Beauty Patter" (Ziatype in vintage case)